Struvite Crystals and Stones

Preventing and treating struvite crystals and stones

Article by CJ Puotinen and Mary Straus, published in the Whole Dog Journal, April 2010

Also see these related articles:

Introduction

Humans aren’t the only ones who get kidney and bladder stones. Our dogs develop these painful and dangerous conditions, too. But much of what is said and done about canine urinary tract stone disease (also known as bladder stones, urolithiasis, urinary stones, ureteral stones, urinary calculi, ureteral calculi, or urinary calculus disease), including its causes and treatment, is either incorrect, ineffective, or potentially harmful. Here’s the information you need in order to make informed decisions on behalf of your best friend.

Most canine uroliths, or bladder stones, fall into six categories, depending on their mineral composition:

- Magnesium ammonium phosphate (also called struvites)

- Calcium oxalate

- Ammonium urate or uric acid

- Cystine

- Calcium phosphate

- Silica.

There are also compound or mixed stones consisting of a core mineral surrounded by smaller amounts of another mineral, most commonly a struvite core surrounded by calcium phosphate. In veterinary reports, the terms stone, urolith, and calculus (its plural is calculi) are used synonymously.

Because different stones require entirely different treatment – and often completely opposite treatment – it’s critical to identify the type of stone accurately. Without removing a stone there is no way to know for sure, but a good guess can be made based on urinary pH; the dog’s age, breed, and sex; type of crystals, if present; radiographic density (how well the stones can be seen on x-ray); whether infection is present; and certain blood test abnormalities.

Between 1981 and 2007, the Minnesota Urolith Center at the University of Minnesota’s College of Veterinary Medicine analyzed 350,803 canine uroliths. The highest percentage came from mixed breeds (25 percent), Miniature Schnauzers (12 percent), Shih Tzus (9 percent), Bichon Frises (7 percent), Cocker Spaniels (5 percent), and Lhasa Apsos (4 percent). The remaining 38 percent were collected from 154 different breeds.

Veterinary studies conducted around the world on millions of urinary stones show similar demographics. Although kidney and bladder stones can afflict dogs of both sexes, all breeds, and all ages, those at greatest risk are small, female, between the ages of 4 and 8, and prone to bladder infections. Although male dogs develop fewer stones, the condition is more dangerous to them because of their anatomy. Stones are more likely to cause blockages in the male’s longer, narrower urethra.

In 1981, 78 percent of all uroliths tested at the Minnesota Urolith Center were struvites and only 5 percent were calcium oxalate stones, but by 2006 the struvite occurrence had fallen to 39 percent while the incidence of calcium oxalate stones rose to 41 percent. Researchers investigating the trend have not discovered a reason for the change but are exploring demographic risk factors such as breed, age, gender anatomy, and genetic predisposition along with environmental risk factors such as sources of food, water, exposure to certain drugs, and living conditions.

Bladder stones

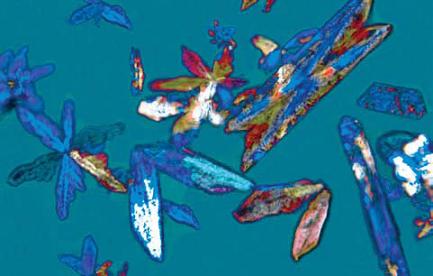

When bladder stones form, their minerals precipitate out in the urine as microscopic crystals. If the crystals unite, they form small grains of sand-like material. Once grains develop, additional precipitation can lead the crystals to adhere together, creating stones. Some stones measure up to 3 or 4 inches in diameter. Problems develop when stones interfere with urination.

Some dogs with stones never develop symptoms and their stones are never diagnosed or are discovered during routine physical exams when the abdomen is palpated. X-rays, which can be used to confirm the diagnosis, reveal stones as obvious white circles unless they are radiolucent (invisible to X-rays), in which case a dye injected into the bladder makes them visible.

Symptoms of stones can include blood in the urine (hematuria), the frequent passing of small amounts of urine, straining to produce urine while holding the position much longer than usual, licking the genital area more than usual, painful urination (the dog yelps from discomfort), cloudy and foul-smelling urine that may contain blood or pus, tenderness in the bladder area, pain in the lower back, fever, and lethargy. If a stone blocks the flow of urine, its complications can be fatal.

When surgery is necessary, uroliths are removed by a cystotomy, a procedure that opens the bladder. Stones lodged in the urethra can be flushed into the bladder and removed. Stones that are small enough to pass in the urine can be removed in a nonsurgical procedure called urohydropropulsion. A catheter is used to fill the sedated dog’s bladder with a saline solution and the bladder is squeezed to expel the stones through the urethra. Other procedures are used for more complicated cases.

All dogs who have formed a urolith are considered at increased risk for a recurrence. According to Dennis J. Chew, DVM, in a paper delivered at the 2004 Small Animal Proceedings Symposium of the American College of Veterinary Surgeons, “Water may be the most important nutrient to prevent recurrence of urolith. Increased water intake is the cornerstone of therapy for urolithiasis in both human and veterinary medicine. Increasing water intake to dilute urine and increase frequency of urination is an important part of treatment. Decreasing the concentration of potential stone-forming minerals in urine and increasing the frequency of voiding are the key elements of therapy to reduce the risk of formation of a new urolith.”

Update: See The Not So Secret Solution for Urinary Crystals in Pets for a veterinarian's advice: "Special diets limit certain minerals and manipulate the ingredients to create a urine pH (measurement of acidity or alkalinity) that is unfavorable for crystals and stones to form. Those of you with pets that have had multiple surgeries to remove bladder stones are well aware of the limitations of these diets to successfully prevent stone formation. The answer appears to be water, H2O, and more water."

It’s easy to interest most dogs in drinking more fluids by making sure that plain water is available at all times, adding broth and other flavor enhancers to water in an additional bowl (see Snack Water), and adding water or broth to food. Just as important is the opportunity to urinate several times a day. Stones and crystals form in supersaturated urine, which can occur when dogs have to hold their urine for long periods.

This month, we’ll discuss struvite uroliths. Calcium oxalate uroliths will be discussed in the next issue.

Struvite stones

Struvite uroliths belong to the magnesium ammonium phosphate (MAP) category. Struvites are also known as triple phosphate uroliths, a term dating from an old, incorrect assumption that the struvite crystal’s phosphate ion was bound to three positive ions instead of just magnesium and ammonium. Although struvites can develop in the kidneys, where they are called nephroliths, the vast majority are bladder stones. About 85 percent of all struvite stones are found in female dogs and only 15 percent are found in males.

Struvite stones usually form when large amounts of crystals are present in combination with a urinary tract infection from urease-producing bacteria such as Staphylococcus or Proteus. Urease is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea, forming ammonia and carbon dioxide. It contributes to struvite stone formation as well as alkaline (high-pH) urine.

Caregivers and veterinarians obviously want to prevent and treat struvites as effectively as possible. But what works and what doesn’t is a topic of confusion.

Fact or fiction

All of the following statements are believed by many veterinarians and their clients. Yet none of them are true. Which have you heard before?

1. Urinary struvite crystals represent disease and require treatment.

2. Struvite crystals require a change in diet, usually to a prescription diet like c/d, u/d, or s/d.

3. Dogs prone to forming struvite stones should be kept on a special diet for life.

4. The most important treatment for dogs with a history of struvite stones is a low-protein diet.

Here’s what's wrong with these common misconceptions:

The presence of urinary struvite crystals alone does not represent disease and does not require treatment. These crystals can be found in the urine of an estimated 40 to 44 percent of all healthy dogs and are not a cause for concern unless accompanied by signs of a urinary tract infection. According to the Merck Veterinary Manual (2005), “Struvite crystals are commonly observed in canine and feline urine. Struvite crystalluria in dogs is not a problem unless there is a concurrent bacterial urinary tract infection with a urease-producing microbe. Without an infection, struvite crystals in dogs will not be associated with struvite urolith formation.” (Our emphasis).

Whether your struvite-crystal dog has a urinary tract infection is the key question. Researchers estimate that more than 98 percent of all struvite stones are associated with infection. Failing to eradicate the original infection and prevent new bacterial infections is the main reason struvite uroliths recur. A recurrence rate of 21 percent was recorded in one study, but the risk can be significantly reduced through increased surveillance and appropriate antimicrobial treatment. In one study, dogs were infected with an experimental Staphylococcal urinary tract infection, and their infection- induced struvites grew large enough to be seen on X-rays within two to eight weeks.

Struvite crystals do not require a change in diet. Because struvite crystals do not pose a problem unless the dog has a urinary tract infection, there is no required treatment for crystals, including dietary changes. If the dog does have a urinary tract infection, a prescription dog food will not cure it.

If your veterinarian finds struvite crystals in the urine and suggests a diet change , you'd be well advised to find a new vet. You have to wonder how many other things he or she is misinformed about. It isn't just a case of not keeping up with newer research; this recommendation is just plain wrong.

Dogs prone to forming struvite stones should not be kept on a special diet for life. Struvites almost always form because of infections, for which dogs with a history of stones should be closely monitored and properly treated. No long-term dietary change is required, nor will a special diet prevent the formation of infection-induced struvites. However, short-term changes may help speed the dissolution of stones.

Low-protein diets do not prevent stone formation. A low-protein diet can speed the dissolution of struvite stones -- when accompanied by appropriate antibiotic treatment -- but it is not necessary for the prevention of struvite formation in dogs who are prone to this problem. For almost all dogs, controlling infections will prevent more stones from forming.

The lowdown on low-protein

Several prescription dog foods are marketed as a treatment for struvite crystals and struvite stones. These are called calculolytic foods or diets, and nearly all of them are severely protein-restricted, phosphate-restricted, magnesium-restricted, acidifying, and supplemented with salt to increase the patient’s thirst and fluid consumption.

While a low-protein diet is not required to dissolve struvite stones, it can speed their dissolution (when accompanied by appropriate antibiotic therapy). Protein provides urea, which bacteria convert or “hydrolyze” into ammonia, one of the struvite building blocks. However, this approach is not a long-term solution and will not prevent the formation of infection-induced stones. Feeding a low-protein diet to an adult dog to help dissolve stones is acceptable for short periods, but because they are not nutritionally complete, low-protein foods are harmful to adults if used for more than a few months, and they should never be fed to puppies.

If stones are not present, there is no reason to feed a low-protein diet. According to Dr. Chew, “No studies exist to show that a specific diet is helpful for the prevention of infection-related stone development.”

In general, the benefits of a meat-based diet far outweigh the risks posed by protein’s ammonia generation. Plus, by feeding your dog a home-prepared diet of fresh ingredients, you can provide food that is higher in quality and much more to your dog’s liking than diets that come out of cans or packages.

Other prescription pet food strategies – such as keeping the diet low in fiber so that fluids are not lost through the intestines, using highly digestible ingredients for the same reason, and increasing the dog’s fluid intake by adding salt to the diet – can be better accomplished with a home-prepared diet and management techniques that encourage the dog to drink more water. The more concentrated the urine, the more saturated it becomes with minerals that can precipitate out, so extra fluids, which dilute the urine, reduce the risk.

Urinary acidifiers are not used to dissolve or prevent stones caused by urinary tract infections, since acidification does not help while an infection is present.

Update: Hill's has introduced new foods for cats with FLUTD (feline lower urinary tract disease) called Hill's Prescription Diet c/d Multicare Feline Urinary Tract Health. These foods are "Clinically tested to dissolve struvite uroliths in as little as 7 days (Average 28 days)." They are high in protein (average 34% on a dry matter basis). While cats are prone to sterile struvites much more than dogs, these foods might work to help quickly dissolve existing stones without having to feed Hill's s/d, which is low in protein and not a complete diet. As far as I know, this food should be safe to feed to adult dogs in the short term (a few weeks to a few months).

The importance of testing

It’s important to know that urinalysis can't always detect a bladder infection; urinalysis may appear normal as frequently as 20 percent of the time when a urinary tract infection is present.

For this reason, if your dog shows possible signs of infection, you need to request a “urinary culture and sensitivity test.” This will verify the diagnosis (in some cases the problem is something other than an infection) and, if it is an infection, it will reveal which antibiotic will be most effective for treatment. Using an ineffective antibiotic not only harms the patient by delaying proper treatment, but also contributes to the spread of drug-resistant bacteria. Antibiotic therapy must be continued as long as struvite stones are present, since the stones harbor bacteria that are released as the stones dissolve.

Dogs who are prone to frequent infections may need longer antibiotic therapy -- of at least four to six weeks -- to completely eradicate the infection. Some dogs need continuous or “pulsed” antibiotic therapy to prevent recurring infections. A few may need surgery to correct structural defects that make them prone to infection, such as a recessed vulva. This condition usually corrects itself following first heat but may continue to cause problems for females who are spayed prior to their first heat. (If needed, surgery called episioplasty can be done to correct this condition.)

Ureaplasma bacteria, which can cause struvite stones, will not show up on a regular urine culture, but you can request a special culture to look for this type of bacteria. This should be done before one assumes that the patient’s struvites are sterile (see Sterile Struvites below) rather than infection-induced.

Follow-up tests will show whether the therapy your dog received, such as antibiotics from a conventional veterinarian or alternative infection-fighting treatment from a holistic vet, was effective. You want to be sure that the treatment worked and that the infection isn’t coming back. For dogs with a history of forming struvite stones, or who suffer from multiple urinary tract infections, cultures should be repeated a few days after treatment ends and then periodically, such as monthly for a while and then at longer intervals, to be sure the infection is completely cleared.

Update December 2019: See Managing recurrent UTIs in pets for insights into this frustrating condition.

At-home prevention

To keep your dog healthy, it’s important to prevent the conditions – especially, urinary tract infections -- that can lead to stone formation.

Monitoring your dog’s urinary pH at home will alert you to any recurring bladder infection. (Sources for pH test strips that cover the range needed are listed below under Resources). The numbers refer to acidity and alkalinity, with 7 considered neutral (neither acid nor alkaline). Numbers less than 7 indicate acidity, and the lower the number, the more acid the substance. Numbers greater than 7 indicate alkalinity, and the higher the number, the more alkaline the substance. Most healthy dogs have a neutral to slightly acid urinary pH between 5.5 and 7.0.

Because urinary pH varies throughout the day, test your dog’s urine at the same time each day to determine her “normal” pH. The best time to do this is first thing in the morning, before she eats. Urine should be tested before it hits the ground. You can collect some in a paper cup or simply hold a pH test strip in the stream. An advantage to paper cup collection is that you can also check the urine for blood, cloudiness, and other indications of infection.

The urinary tract infections that cause struvite crystals to become uroliths have an alkalizing effect, raising urinary pH to as much as 8.0 or 8.5. If your dog’s urinary pH jumps from acid to alkaline, contact your veterinarian.

Other preventive measures include giving your dog cranberry capsules, probiotics, and vitamin C.

Cranberry doesn’t cure existing infections, but it mechanically prevents bacteria from adhering to the tissue that lines the bladder and urinary tract. Because they are continuously washed out of the system, bacteria don’t have an opportunity to create new infections. Cranberry capsules are easier to use and more effective than juice, since they are far more concentrated. On product labels, the terms cranberry, cranberry juice, cranberry extract, and cranberry concentrate tend to be used interchangeably. D-mannose, a natural sugar extracted from cranberry and other fruits, can also be used to help prevent bladder infections by the same means. See Urinary Tract Infections & D-Mannose for more information.

If your cranberry capsules are a veterinary product, follow label directions. If they're designed for humans, adjust the dosage for your dog’s weight by assuming that the label dose applies to a human weighing 100-120 pounds. Giving cranberry in divided doses, such as twice or three times during the day, will make this preventative treatment more effective.

Probiotics are the body’s first line of defense against infection, and the more beneficial bacteria in your dog’s digestive tract, the better. Probiotics are routinely used by a growing number of medical doctors and veterinarians to treat urinary tract and vaginal infections in women and pets.

Several brands of probiotics are made especially for dogs. Because antibiotics destroy beneficial as well as harmful bacteria, the use of probiotic supplements after treatment with antibiotics helps restore the body’s population of beneficial bacteria. (See Probing Probiotics, Whole Dog Journal August 2006, for more information.)

Many veterinarians recommend vitamin C for dogs who are prone to bladder infections and struvite stones because of its anti-inflammatory effects. Dogs (unlike humans) do manufacture their own vitamin C, but the amount they produce may not meet their needs if they are under stress or fighting infection.

The ascorbate form of vitamin C is most often recommended for dogs, as it may be better absorbed and is less prone to causing gastrointestinal upset . Calcium ascorbate and sodium ascorbate are available in generic forms as a powder, but the most popular form is a product called Ester-C, which contains calcium ascorbate and vitamin C metabolites.

Veterinary recommendations range from 250 mg twice per day for every 15 to 30 pounds of body weight up to a maximum of 1,000 mg twice a day for large dogs. Because vitamin C can cause diarrhea, start with small doses and increase gradually. The maximum amount your dog can tolerate without the diarrhea side effect is called her “bowel tolerance” dose.

The herb uva ursi (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) is used in many herbal blends for bladder infections because of its antibacterial properties. Uva ursi is best used for short periods rather than for months at a time as it can irritate the kidneys. The dosage for this herb depends on the individual blend and how it was prepared. Follow label directions for products formulated for dogs; adjust the dosage of products meant for humans by weight, assuming the human’s weight at 100 to 120 pounds.

There are also herbal blends in tincture form that contain uva ursi or other herbs that may help protect against bladder infections. Examples include Animals' Apawthecary's Tinkle Tonic and Azmira's Kidni Biotic.

While adding salt to your dog’s food is an effective way to encourage drinking more fluids for dogs who don't tend to drink enough, consider switching from refined table salt to unrefined sea salt, which is sold in natural food markets and contains dozens of minerals and trace elements that are not present in refined salt.

Since most homemade diets are low in salt compared to commercial foods, the amount of salt to add will depend on the diet you feed. Start by adding a pinch of salt (small for a small dog, larger for a large dog) to your dog’s food and watch to see if it makes her more thirsty. Increase the amount by a pinch at a time until she is drinking more than usual.

Traditional broth or stock is easy to make at home by simmering chicken, beef, or other bones in water overnight or for 24 to 36 hours. If desired, add carrots and other vegetables. Replace evaporating water as needed. The longer the simmer, the more nutritionally dense the broth and the more interesting it is likely to be to your dog. Broth can be used as a flavor enhancer when strained and added to food or given in addition to water. Be sure to provide plain drinking water at all times.

Struvite stones can make any dog miserable, but by understanding how and why they occur and by taking the preventive measures described here, you can be sure that your dog lives a happy, stone-free life.

I regret that I no longer have much time to respond to questions. See my Contact page for more information. My name is Mary Straus and you can email me at either or