My Visit to Wolf Park, June 2001

In October, 1997, I attended a five-day Wolf Behavior Seminar at Wolf Park in Indiana. It changed my life. Not only did I learn a tremendous amount about wolf behavior, but it started me on the road to raw feeding my own dogs, clicker training, and gaining a much better understanding of dog body language from the works of Turid Rugaas. I have wanted to go back ever since. I thought I would get over it in time, but instead, the yearning actually became greater, so finally, 3 1/2 years later, I returned to Wolf Park.

I was privileged to spend most of the day on Monday and part of Tuesday at the park with the wolves. It was the first really hot days of the season, so no one was very active. I got to go in with several different wolves, plus the coyote and the foxes, everything went very smoothly even when I was stupid and leaned over one of them to brush flies away.

The wolves are fascinating to look at and observe. They are long legged and long bodied, incredibly tall when they stand on their hind legs, but very narrow and cow-hocked (hocks turn in and feet turn out) -- I find it interesting that their build is so different from what most breed standards in dogs are looking for. One of the wolf researchers thinks that the original purebred standards may have been developed by people who were more experienced with horse conformation, so we look more for structure that is good on horses, maybe not so natural for dogs. Just a thought, I have no idea myself, just know that wolves are made to be able to travel many miles every day with their ground-eating trot.

The wolves are fascinating to look at and observe. They are long legged and long bodied, incredibly tall when they stand on their hind legs, but very narrow and cow-hocked (hocks turn in and feet turn out) -- I find it interesting that their build is so different from what most breed standards in dogs are looking for. One of the wolf researchers thinks that the original purebred standards may have been developed by people who were more experienced with horse conformation, so we look more for structure that is good on horses, maybe not so natural for dogs. Just a thought, I have no idea myself, just know that wolves are made to be able to travel many miles every day with their ground-eating trot.

Wolves apparently have much larger heads for their body size than dogs do, one of several differences between them. I was told that a 90 pound wolf has a head the size of a 200 pound dog -- click here for head shots of a wolf and human that give an indication of how big they are. This information is from research done by Ray Coppinger -- I'll be attending a seminar of his in July and hope to learn more. He also has some theories about dogs evolving by hanging around humans and eating garbage, apparently he feels that dogs can survive eating garbage whereas wolves cannot (and they do not do well on kibble at all). I don't think he is claiming a different digestive system, it may be more a process of selection, the ones that could handle eating garbage survived and continued to hang around humans, while ones that could not handle it did not survive to pass along their genes. I really don't understand that much of the theory (and am not yet sure what my own opinion of it is).

The wolves at the park are fed mostly deer, from road kill. They brought in a carcass while I was there, fascinating to watch. The alpha female went over and tore open the throat and began eating the muscle meat from the neck and shoulder, exposing the ribcage. She had to work at it, bracing herself and pulling to get the hide out of the way and rip off pieces of meat. Her muzzle was red (reminded me of the infamous dogs in elk story). Apparently, muscle meat is considered the choicest part of the carcass -- I asked about organ meats, and was told that they will tend to eat those first if they have not had organ meat for awhile. These wolves do not eat the stomach contents at all and only sometimes eat the intestines and the harder bones, like the leg bones, depends on how hungry they are. Sometimes, when food is plentiful, they don't eat that many bones, but other times they will finish off a whole carcass (except for the stomach). Another wolf came up when the alpha female was done and pulled off the tail and munched on part of it, then ate some meat from the hindquarters. They said that wild animals open the belly first because the skin is thinnest there and easiest to open -- at the park, they make a few cuts in the hide with a butcher knife to make the access easier, which may explain why neither of these two started with the belly.

The wolves at the park are fed mostly deer, from road kill. They brought in a carcass while I was there, fascinating to watch. The alpha female went over and tore open the throat and began eating the muscle meat from the neck and shoulder, exposing the ribcage. She had to work at it, bracing herself and pulling to get the hide out of the way and rip off pieces of meat. Her muzzle was red (reminded me of the infamous dogs in elk story). Apparently, muscle meat is considered the choicest part of the carcass -- I asked about organ meats, and was told that they will tend to eat those first if they have not had organ meat for awhile. These wolves do not eat the stomach contents at all and only sometimes eat the intestines and the harder bones, like the leg bones, depends on how hungry they are. Sometimes, when food is plentiful, they don't eat that many bones, but other times they will finish off a whole carcass (except for the stomach). Another wolf came up when the alpha female was done and pulled off the tail and munched on part of it, then ate some meat from the hindquarters. They said that wild animals open the belly first because the skin is thinnest there and easiest to open -- at the park, they make a few cuts in the hide with a butcher knife to make the access easier, which may explain why neither of these two started with the belly.

The wolves are only fed three times a week, though they may eat parts of the carcass that are left over on other days. The carcasses are ripe and stinky and sit out in the sun with flies on them, doesn't bother the wolves at all and I've never heard of them having trouble with bacteria. All the wolves had been eating well, I noticed that any extra weight showed up underneath, where the loin was not as tucked up, rather than looking wider -- wolves are very narrow. The smallest, skinniest wolf is apparently the biggest eater, she's the alpha female, weighs about 70 pounds and is very active. The larger wolves weigh up to about 90 pounds, although apparently there are wolves elsewhere that get as high as 120-130 pounds.

The wolves' feet are huge, which I guess helps them walk in snow and makes them great swimmers -- they love the water and I watched one paddling happily around in the lake in the main enclosure. They had lost their Winter coats and looked somewhat scraggly (it also makes the heads look even bigger). In Winter, the coats are so thick and well insulated that they have been seen playing contentedly in temperatures of 10 degrees below zero, with wind chill factor at 60 degrees below. So little heat escapes from their bodies that snow does not even melt on their coats. If they fall thru the ice into the water, they don't even get wet. They said that in Winter, the coats are so buoyant that about 10 inches of the wolf stays above water while swimming, whereas in Summer, only the head is above water.

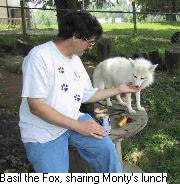

The oldest wolf at the Park turned 17 in April (wolves are born only in April or early May, they have only one breeding season a year, in February), but she has cancer and will not live much longer. They have several others that are 11 to 13 and doing well. Wild Bill, the coyote, is 14 and looks great. I was shocked to learn that he weighs less than 30 pounds (he is small for a coyote but he looks much larger than my 34 pound dog, Piglet, who is not overweight). The foxes were even more shocking, apparently weighing only 7-10 pounds, though they look like they would weigh much more.

The oldest wolf at the Park turned 17 in April (wolves are born only in April or early May, they have only one breeding season a year, in February), but she has cancer and will not live much longer. They have several others that are 11 to 13 and doing well. Wild Bill, the coyote, is 14 and looks great. I was shocked to learn that he weighs less than 30 pounds (he is small for a coyote but he looks much larger than my 34 pound dog, Piglet, who is not overweight). The foxes were even more shocking, apparently weighing only 7-10 pounds, though they look like they would weigh much more.

The alpha pair in the main pack are the two smallest wolves in the pack. The male, Seneca, was very smart in his younger days and advanced in rank by taking advantage of other wolves by running over and standing over them when they were submitting to the alpha at the time. He thus rose in rank to #2 (beta) without having to win a fight, and inherited the alpha position when Orca was paralyzed.  He has turned into a very benevolent and well-loved leader; when he came trotting over, he was practically mobbed by the other wolves licking his face and greeting him enthusiastically, which he tolerated with kingly benevolence. It reminded me of how our dogs greet us when we get home -- the wolves didn't act this way with the other wolves or with any of the humans, though they would go up to get scritches from the people they know. These wolves are human-socialized and for the most part friendly, some more so than others, though they are also very likely to pinch (bite, but without breaking skin), sometimes when scared/stressed, but often just to see if they can get a reaction -- wolves like drama and stirring up trouble (again, some more than others). There are several of the wolves that are not allowed to greet visitors, and one that only one person at the Park can go in with at all. Even though socialized from birth, if continual contact and training is not maintained, they lose their socialization and learned behaviors fairly quickly (another difference

He has turned into a very benevolent and well-loved leader; when he came trotting over, he was practically mobbed by the other wolves licking his face and greeting him enthusiastically, which he tolerated with kingly benevolence. It reminded me of how our dogs greet us when we get home -- the wolves didn't act this way with the other wolves or with any of the humans, though they would go up to get scritches from the people they know. These wolves are human-socialized and for the most part friendly, some more so than others, though they are also very likely to pinch (bite, but without breaking skin), sometimes when scared/stressed, but often just to see if they can get a reaction -- wolves like drama and stirring up trouble (again, some more than others). There are several of the wolves that are not allowed to greet visitors, and one that only one person at the Park can go in with at all. Even though socialized from birth, if continual contact and training is not maintained, they lose their socialization and learned behaviors fairly quickly (another difference

between dogs and wolves).

They try to offer the wolves a variety of different things at different times, both for eating and for entertainment. They gave them some chunks of frozen milk while I was there, and are planning a watermelon party for July. When I was there in 1997, they gave them a pumpkin with peanut butter inside, I have some great pictures of the wolves investigating and enjoying this new oddity. They also get a variety of small animal carcasses from nearby Purdue, which has both a veterinary college and an agricultural school. Someone once sent them a large number of frozen chicks, which were a great hit with everyone. They maintain a bison herd at the park, and allow a few of the wolves to go in with the bison, in order to observe their behavior with large prey animals. The bison are in no danger from the wolves (in fact, it's more the other way around), even the calves are fine if they stick with their moms -- when they have very small calves, they tend to bring in the wolves that aren't very good hunters, just to be safe. The wolves will "test" the bison -- looks like they are soliciting play -- if a bison were to act fearful, it might invite an attack, as the wolf would know there was something wrong. Normally, the bison simply stand their ground, or charge at the wolves, who duck out of the way. Once, they put a stuffed wolf hide in with the bison, who stomped and gored it repeatedly. One of the bison choked to death on his cud awhile back, so they butchered it and offered the meat to the wolves, who all refused to eat it, no idea why.

I really recommend a visit if you're ever in Indiana. They are open to the public in the warmer months. If you sponsor a wolf for $145 a year, it earns you the right to go in and visit with your wolf (or a suitable alternate, if your wolf is not considered greetable). They also offer behavior seminars several times a year, including a combined seminar on dogs and wolves with Terry Ryan every June. Monty Sloan offers Photo Seminars and Shoots with the wolves as well. You can see a number of photographs at Monty Sloan's website.

I regret that I no longer have much time to respond to questions. See my Contact page for more information. My name is Mary Straus and you can email me at either or